|

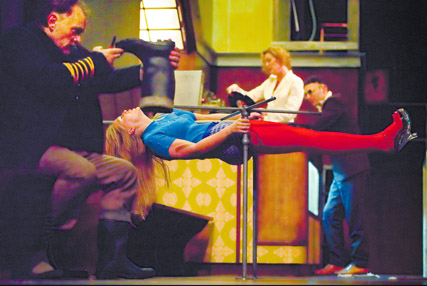

Seemannslieder photo Phile Deprez |

Born, in Erlenbach near Zurich, in 1951, Marthaler is a classically trained musician. He began to develop his distinctive theatre language working in Basel between 1980 and 1988 with a series of music theatre compositions and song recitals. These included collages of various folk songs and evenings after Erik Satie, John Cage and Kurt Schwitters. The title of his song project on the Swiss military, Wenn das Alpenhirin sich rötet, tötet, freie Schweizer, tötet... [When the Alpine mind reddens, Kill free Swiss, Kill], mocked the Swiss national anthem and nearly caused the sacking of the theatre’s artistic director.

Since the early 1990s, Marthaler has created theatre works for Berlin’s Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, Deutsches Schauspielhaus in Hamburg and Schauspielhaus Zurich where he was artistic director 2000-2004. He has directed many operas including Pelléas et Mélisande, Fidelio, Katja Kabanowa, Pierrot Lunaire and, most recently, Tristan und Isolde at Bayreuth. His award-winning theatre productions are regularly invited to the Berlin Theatertreffen and to festivals worldwide.

All Marthaler’s work must be considered music theatre. As a composer, he develops a score of gesture, speech, music and behaviour. Text and narrative are subordinated to rhythmic compositions, self-repeating segments and enactments of ‘dead’ time. His use of live music is always extremely playful and choral arrangements of songs are present throughout all his works. This is equally true of his versions of plays—including Chekhov’s Drei Schwestern [Three Sisters]; Horvath’s Kasimir und Karoline; Zur Schönen Aussicht [To the Beautiful Prospect]; Dantons Tod [Danton’s Death] by Buchner—as of his found text assemblages—including Die Stunde Null [The Zero Hour] devised from speeches by post-war German politicians; Groundings, concerning the decline of the Swiss airline industry; or Die Fruchtfliege about the life cycle of the fruitfly. It is also true of his song-collage projects—such as Murx den Europäer! Murx ihn! Murx ihn! Murx ihn ab! [Kill the European! Kill him! Kill him! Kill him off!] composed of nostalgic German Volkslied; Die Zehn Geboten [The Ten Commandments] after the songs of Rafaelle Viviani; or his staging of Schubert’s Die Schöne Mullerin. Other composers present in Marthaler’s theatre include Charles Ives, Noël Coward, Lloyd Webber, Monteverdi, Berg, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, Offenbach, Puccini and Verdi, to name a few.

Singing in Marthaler’s theatre occasions acts of collective memory. Mostly sung very quietly, songs grow out of silence bringing individuals from solitude into chorus. They are sung as if half-remembered, very fragile, harmonious and beautiful. Sometimes, they’re like a prayer repeated. Sometimes, a long lost refrain. Every now and then, an aria turns inward. Here and there, a daggy vaudeville turn. They express impossible longings for a lost past and a longed for present.

In Murx! singing constitutes an historical haunting and scouring of national identity. Subtitled Ein patriotischer Abend [A Patriotic Evening], the piece, created in 1992, has been called a requiem for the former East Germany. It takes place in a vast empty hall: some run-down public institution with wood-panelled walls, fluoro lights, an empty elevator moving up and down without passengers, and several huge furnaces which require regular stoking. The clock on the wall has stopped, but a bell repeatedly rings, causing the inhabitants of the room to queue to wash their hands in a washroom upstage. Otherwise, they sit at their respective tables and engage in banal, repetitive rituals, petty spats and obsessive acts. Only when they sing are they united. The Volkslieder sung in Murx! carry repressed memories of Germany’s fascist past and connotations of the still open wound of reunification. Songs of glorified nationalism lose all innocence and even the very act of singing recalls the use of such songs in Third Reich rallies. At one stage, two of the actors play klezmer music, at first very softly, then others take it up, and for a while, it fills the hall. It hangs in the air like a beautiful memory. The furnaces on the side of the stage are stoked. The song seems to escape from within. In the memory time of the song, voice becomes an act of ghosting, a prayer in a room where clock time has stalled.

A few years before, in 1992, with a version of Labiche’s Die Affäre Rue de Lourcine, Marthaler commenced his collaboration with set and costume designer Anna Viebrock. For over 15 years across opera and theatre, they have staged variations of the same banal room peopled by fragile communities of melancholic, washed up figures. Their body of work is a continuing articulation of recurring ideas and states. Uninterested in novelty or reinvention, Marthaler patiently elaborates his alternate temporal order in Viebrock’s empty rooms.

Every set which Viebrock designs is a waiting room of some kind. Like the spaces photographed by Candida Höfer, the rooms which Viebrock places onstage posit an architecture of absence. Belonging to a recent past, often institutional, her rooms contain an air of slowness, of deliberation, of space remembered—an old sound recording studio, a disused factory, a wood panelled ballroom, an emptied library, the stairwell of an apartment block, the stage of a community hall, a foyer. Often, Viebrock’s stages begin as copies or translations of found spaces, old photographs or abandoned buildings. Her rooms, though concrete in detail and autonomous in presence, are often ambiguous. They contain traces of multiple uses, or overlap heterogeneous spaces, as in the room of Die Zehn Geboten which crossbreeds the nave of a cathedral with a dusty old stage. All Viebrock’s rooms bear the marks of their use and the wear of time. Their furnishings are dilapidated. The people too have a sense of being left behind. Their clothes place them in another era, yet they never belong to ‘period pieces.’ According to theatre writer Stephanie Carp, they are “remembered and dreamed people”, necessarily familiar. So, Chekhov’s Prozorov sisters might be recognised “crossing Alexanderplatz holding plastic bags at the close of a workday.”

Marthaler always places a community on stage. His people are alone together. Found in Viebrock’s rooms they are subject to the same laws of entropy. In this sense, as in his stagings of Horvath, all Marthaler’s pieces are folk plays concerned with forgotten people, language collapsing into silence, a persistence of song and a poetry of the everyday. An affinity with Chekhov resounds in shared concepts of organic communities and the cyclic nature of time. Marthaler extends the powerlessness of his onstage figures resulting in a deepened abnegation of climax and suspense in favour of a draining of drama. When the figures in his Three Sisters wish for a glorious future, it is already a memory, a function of lapsed ideology and actions long faded into routine.

This theatre of quiet, slow life enacts a withdrawal of drama from the stage. The figures onstage are withdrawn too. Unable to play heroes, they wait their entire lives for something that never comes. It even seems as if they would rather not be on stage. They stare into corners, face the wall, perform exercises, quietly recite old texts. Every now and then someone trips, or a glass breaks, or a sudden fit disturbs compulsive patterns.

The Marthaler family of actors (including André Jung, Ueli Jäggi, Olivia Grigolli, Matthias Matschke, Judith Engel, Jean-Pierre Cornu, and Graham F Valentine) are all great, gentle clowns. Onstage they are unforced, light, always playful and often very funny. Through little quirks, obsessive routines and their shared songs, they form Marthaler’s island of stranded people. People who are unable to belong in the shiny world of advertising. People whom the rush of capitalism leaves behind. From their silence, Christoph Marthaler extracts frailty, neurosis and longing. He finds the beauty of the powerless.

Speaking at the start of rehearsals for a new work, Winch Only (premiered in Brussels in May 2006), Marthaler said, “We still don’t know what we’re going to do. The prerequisite first of all is to create a real group of actors capable of understanding each other and what everyone’s feeling. And the best way to do that is to sing and eat together! We sing a lot and improvise. We always do that when we’re not dealing with specific work on a play or opera. We have to get to know each other and our voices first.”

Marthaler’s music theatre shares Italo Calvino’s favourite motto, ‘festina lente’, hurry slowly. Against capitalism’s perpetual novelty and urge to speed, he allows theatre to maintain a distinct tempo. He slows the heartbeat and stops life’s flow to observe and reflect. Duration is staged as a musical melody, a multiplicity and a dynamic continuation of past into present time into a future. Marthaler’s humanist theatre is a refusal to speed up or catch up.

ZT Hollandia/NTGent, Seemannslieder, director Christoph Marthaler, designer Anna Viebrock, Sydney Theatre, Jan 10-13,

www.sydneyfestival.org.au

Benedict Andrews directs for Sydney Theatre Company [in 2007, Patrick White’s The Season at Sarsaparilla]; Company B [Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf]; Malthouse, Melbourne and the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz, Berlin.

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 8

© Benedict Andrews; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back