|

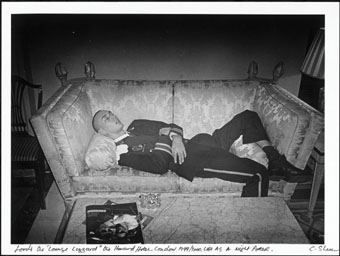

Chris Shaw, from Life as a Night Porter series, 1999-2000 |

Sometimes this device works most effectively from a distance, as with Annie Hogan’s large-scale interiors, Harmony and Disposition (2002), where windows filter streams of Queensland light into the uninhabited rooms of rental homes. Hogan is concerned with the way the domestic interior is “imprinted” with “past actions and energy...long after its inhabitants have departed.” The gallery light, ushering us closer, fading and blazing, adds a cinematic quality, enhancing our sense of time passing.

|

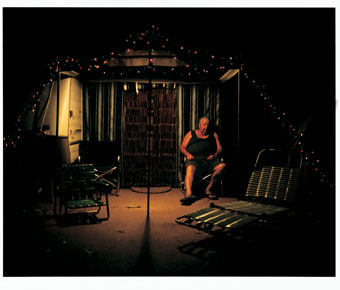

Matthew Sleeth, Untitled #26, Rosebud series, 2003/2004, type C photograph |

Nearby, a wall of portraits snare me in deeper thought. It’s 1964 and Robert McFarlane has snapped Charles Perkins travelling to University, 1963, a photograph that prefigures Perkins’ passionate, activist future. He’s young and handsome in black and white, pensively biting his thumbnail. The bus makes me think of the 1966 Freedom Rides to country towns like Moree, where Perkins and a mob of Aboriginal kids were barred from entering the local pool: “Sorry, darkies not allowed in.” (Elsewhere in the exhibition, another historic moment in black/white relations: Mervyn Bishop’s shot of Gough Whitlam granting traditional lands to the Gurindji in a symbolic exchange with elder Vincent Lingiari in 1975 while cameras send off tiny flares in the night.) The Perkins image makes me profoundly melancholy. It’s barely a month after the election—which made no reference to any Indigenous issues—the Coalition dismantling ATSIC and Perkins, once deputy chair of the Commission, has passed away.

My feeling is intensified by the adjacent print—Mervyn Fitzhenry’s Old man with Cat (1996). Man and cat sit on separate armchairs in a bare, formerly grand room. His busted shoes are unlaced, the cat is poised and delicate like an incarnation from another lifetime (but we suspect it was she who ripped the stuffing from the arm of his ragged chair). Another shot by McFarlane shows Robyn Archer in Kold Komfort Kaffee Nimrod Theatre (1978). In full pancake makeup, hair slicked back, Archer reminds me of a broken Liza Minelli at the end of Cabaret. There’s an ephemeral darkness suggested by this line of prints, of politics and fate, of inevitable, imminent moments.

In a cheerier passage, Patrica Piccinini’s glossy prints show tracts of female skin (Subset Green Body, 1997) glowing with a honeyed light, and, of course, the plastic flesh of her hybrid creatures. “I like rats with ears” someone writes of these monsters in the comments book, and “I like female hands.” Someone else declares the exhibit “almost Caravaggio”, probably referring to the Bill Henson prints that fill another room, or Sleeth’s work, which is equally chiaroscuro. Henson’s now famous sultry, sulky adolescents loom out of inky backgrounds that further emphasise their suspension between child and adult. Lights here are faint glows or decorative spangles forming a sequined horizon. Henson’s kids languish beside deeply eerie landscapes where distant industries send flares and swathes of lambent light into night skies (Untitled, 1998/99). His suburbs have a foreboding quality, enhanced by a murky pre-dawn. On Garnett St (Untitled, 1985/6) the Neighbourhood Watch sign seems more ominous than reassuring. Its silhouetted police and citizen heads watch over the sleeping suburb while 3 distant electricity towers appear to advance, like space creatures with steely arms in the air.

Though Ross Gibson knows not everyone likes their modernist white gallery spaces messed with, as curator at a university gallery his job was not just to consider “how best to serve the work”, but given the research context, to experiment. The result compels me to adopt a kind of moving meditation that creates a slipstream of connections, between say the Perkins portrait and the Lingiari shot. It makes me consider all sorts of darkness: from the literally black backgrounds, shadows and chiaroscuro in many of these works, to the void into which significant cultural moments, histories and figures seem to have disappeared.

The decidedly unheimlich colour work of Aboriginal artist Darren Siwes features in both the UTS show and Night Visions at the Australian Centre for Photography. Siwes appears as a masked ghost in the foreground of various sites in London and Australia, suggesting the disappearance or fragility of colonial histories. Night Visions encompasses all kinds of nocturnal preoccupations, from Weegee’s crime scene snaps and Brassai’s romantic pre-war Paris newly illuminated with electricity, to Chris Shaw’s Barton Fink-ish Life as a Night Porter series (1993-2003). Like Siwes’, Shaw’s work is about the unhomely but here it’s the faux-homeyness of hotel lounges, rooms and hallways. Shaw snaps guests and staff in various stages of disrepair against the ubiquitously gaudy wallpaper, carpet and velveteen lounges of London hotels. Beneath each shot, the photographer’s acerbic handwritten observations have the wry, shorthand quality of postcard text. Also featured are some seriously disquieting photos by Corporal Darren Hilder. Taken with military night vision technology, Hilder’s fellow soldiers pose with heavy artillery in dusty landscapes awash with a Martian light.

Written with Darkness, curator Ross Gibson, UTS Gallery, Sydney, Oct 12-Nov 5; Night Visions , curator Alasdair Foster; in partnership with the Australian National Gallery, Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, Oct 1-Nov 14

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004 pg. 50

© Mireille Juchau; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back