|

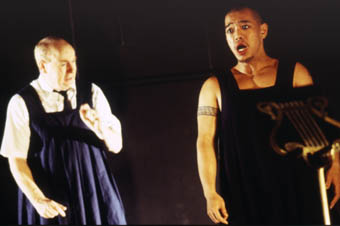

Andrew Morrish, Peretta Anggerek, entertaining paradise photo Heidrun Löhr |

We have been warned. This is not a production of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s play Pre-Paradise Sorry Now, although it does draw on that work for at least part of its organising structure.

‘The cat’ was one of the early victims of Ian Brady who later, with Myra Hindley, terrorised, raped and killed 5 children in England in the 1960s and buried them on the moors. Leaving the cat alone, resisting violence and victimisation, is also an underlying entreaty of this piece which has been created “respecting those we sometimes dismiss as victims or less-than-losers” (program note).

entertaining paradise echoes the Fassbinder play in that it contains sections of narration about the exploits of Ian and Myra (or ‘Mein Führer’ and ‘Hessie’—after Rudolf Hess—as they called one another); dialogue between the 2, and a series of scenes “about the fascistoid underpinnings of everyday life” as Fassbinder saw it.

The ‘everyday life’ which Kellaway chooses to portray is that of the schoolyard—the performers are all costumed (by Annemaree Dalziel) in blue box pleated school tunics, and the piece opens with a giggling schoolyard courtship ritual. Their playground, populated by the loathsome bullies we all remember, is the triangular performance space (piano at its apex, complete with one of the school nerds playing; Michael Bell at the piano), and it is thoughtfully used to mirror the victimisation triangle of 2 ganging up on one. A triangle where allegiances shift suddenly and mercurially among the partners/victims in crime.

Here, the one-time Brady/Hindley victims are the aggressors—not to provide the simplistic excuse of arrested development or childhood trauma for adult atrocities, but perhaps rather to also allow for some timely self-reflection. Adults, of course, should know better than to persecute the innocent, the weak and the different. But are Ian, the bookkeeper and Myra, the secretary so different from the millions of other bookkeepers and secretaries who, closer to home, listen to Alan Jones, vote for John Howard, and hate their neighbours? It is the evil side to their banality that we need to worry about.

At one intriguing moment of the performance, peering deep into their music scores, Ian and Myra perceive the images of their victims. And so too, during this performance, are we uncomfortably reminded of the ugly hearts of glorious cultures that produce Berg and Hitler, Purcell and Brady. Closer to home, what ‘we’ love and hate is, literally, embodied in Indonesian-born Peretta Anggerek: the heights of Western musical culture emanating from the body of a despised and feared Other.

(And this is further subtly reiterated in performance: it is no innocent gesture for Anggerek in his school uniform to quietly read his Tintin book on stage. It points to an insidious and ongoing colonial project, which many seem so reluctant to relinquish. Not for us the putting away of childish things.)

Music is central to The opera Project’s work, and here Michael Bell provides the excellent live accompaniment (everything from Elvis to Berg); and Anggerek’s lovely counter-tenor is a pleasure in and of itself, whether he’s singing a traditional Indonesian tune or songs from the Western repertoire.

While an intense engagement with music is familiar territory for Kellaway’s productions, improvisation as a major element is a new departure and an inspired addition. What improvisation can so successfully do, in the face of the other very structured and often technically demanding performance elements (piano playing, opera singing, text-based theatre), is to undo them. It can rewrite and overwrite—it adds the dash of danger, the unexpected swerve, to performances which otherwise have their set paths to follow from beginning to end. And then there is also, simply, the pleasure of watching the performers create as they go, the thrill of the instant response to the immediacy of their situation.

Kellaway and Heilmann are—as always—riveting performers and seeing their work with the Fassbinder text (and especially as Ian and Myra) was enough to make me idly wish—heresy!—for the opportunity to see them do ‘straight’ theatre.

Clever, unexpected, provocative and captivatingly performed by all—I wish I had had the opportunity to return again (and again) as others did to see the re-creation of entertaining paradise each night during its season.

entertaining paradise, The opera Project, director Nigel Kellaway, performers Regina Heilmann, Nigel Kellaway, Andrew Morrish, counter-tenor Peretta Anggerek, pianist Michael Bell, The Performance Space, April 19-26

Laura Ginters lectures in Performance Studies at the University of Sydney and worked, until recently, for Playworks. She has a PhD in Performance Studies and Germanic Studies and has worked as translator and dramaturg for stage productions.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 34

© Laura Ginters; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back